Our History

Our History

Our History

Our History

Our History

Beginnings and Blacksmithery

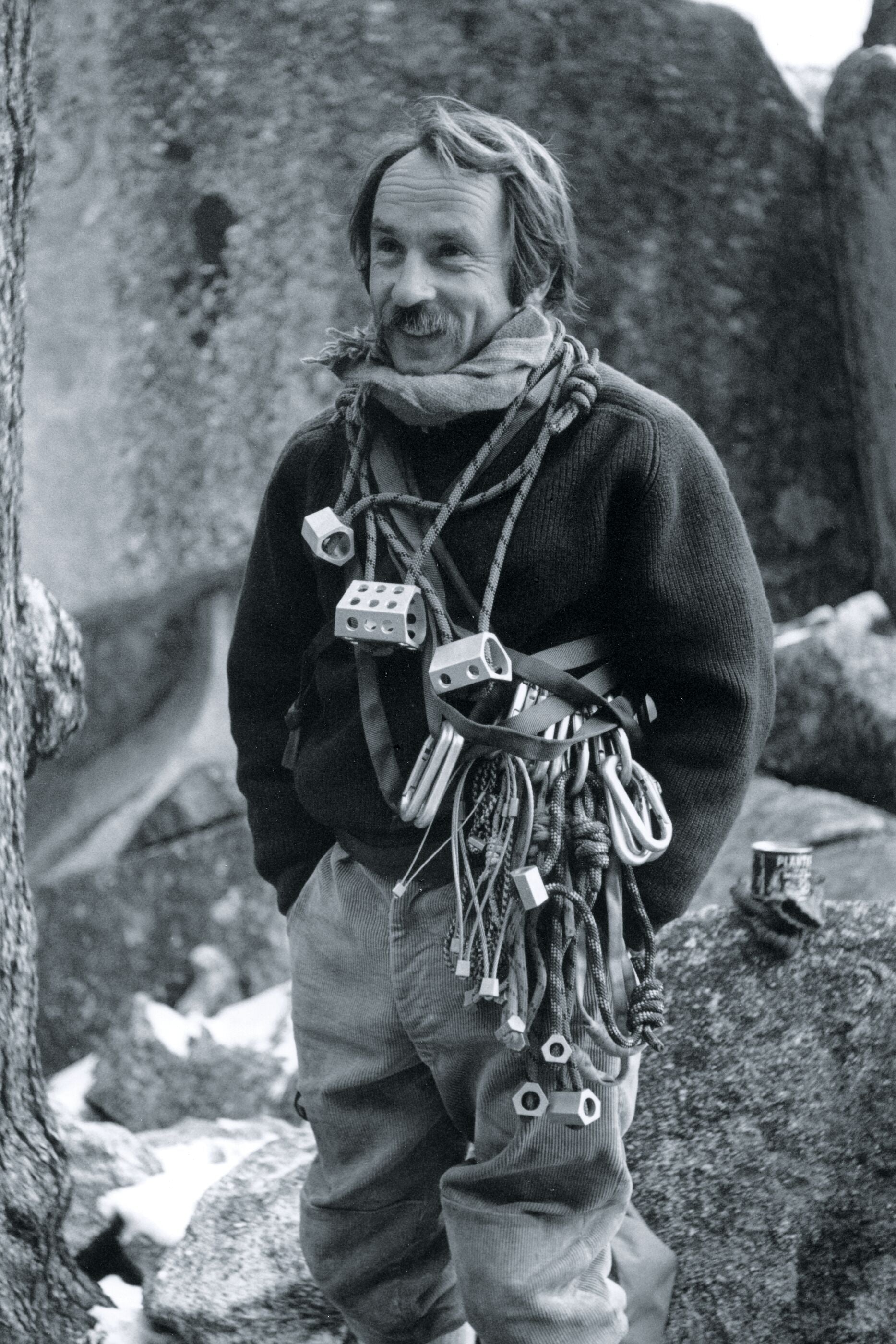

Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia’s founder, got his start as a climber in 1953 as a 14-year-old member of the Southern California Falconry Club. One of the adult leaders, Don Prentice, taught the boys how to rappel down the cliffs to the falcon aeries. This simple lesson sparked a lifelong love of rock climbing in Yvon.

Chouinard started hanging out at Stoney Point and Tahquitz Rock, where he met some other young climbers who belonged to the Sierra Club, including T.M. Herbert, Royal Robbins and Tom Frost. Eventually, the friends moved on from Tahquitz to Yosemite, to teach themselves to climb its big walls.

In 1957, Yvon went to a junkyard and bought a used coal-fired forge, a 138-pound anvil and some tongs and hammers, and started teaching himself how to blacksmith. Chouinard made his first pitons from an old harvester blade and tried them out with T.M. Herbert on early ascents of the Lost Arrow Chimney and the north face of Sentinel Rock in Yosemite.

The word spread and soon friends had to have Chouinard’s chrome-molybdenum steel pitons. Before he knew it, he was in business. He could forge two of his pitons in an hour and sold them for $1.50 each. Chouinard built a small shop in his parents’ backyard in Burbank. Most of his tools were portable, so he could load up his car and travel the California coast from Big Sur to San Diego, surfing.

He supported himself selling gear from the back of his car. The profits were slim, though. Before leaving for the Rockies one summer he bought two cases of dented, canned cat tuna from a damaged-can outlet in San Francisco. This food supply was supplemented by oatmeal, potatoes and poached ground squirrel and porcupines.

In Yosemite, he and his friends had to hide out from the rangers in the boulders above Camp 4 after they overstayed the two-week camping limit. They took pride in the fact that climbing rocks and icefalls had no economic value; that they were rebels. Their heroes were Muir, Thoreau, Emerson, Gaston Rébuffat, Riccardo Cassin and Hermann Buhl.

In 1965, Yvon went into partnership with Tom Frost and started Chouinard Equipment. During the nine years that Frost and Chouinard were partners, they redesigned and improved almost every climbing tool to make them stronger, lighter, simpler and more functional. Their guiding design principle came from Antoine de Saint Exupéry, the French aviator: “In anything at all, perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to take away, when a body has been stripped down to its nakedness.”

By 1970, Chouinard Equipment had become the largest supplier of climbing hardware in the United States. It had also become an environmental villain because its gear was damaging the rock. The same fragile cracks had to endure repeated hammering of pitons during both placement and removal, and the disfiguring was severe. Chouinard and Frost decided to minimize the piton business. This was to be the first big environmental step we would take over the years.

Fortunately, there was an alternative: aluminum chocks that could be wedged by hand rather than hammered in and out of cracks. We introduced them in the first Chouinard Equipment catalog in 1972. A 14-page essay by Sierra climber Doug Robinson on how to use chocks appeared in the catalog, paving the way for future environmental essays in Patagonia catalogs. Within a few months of the catalog’s mailing, the piton business had atrophied; chocks sold faster than they could be made.

Patagonia Software

On a winter climbing trip to Scotland in 1970, Chouinard bought a regulation-team rugby shirt to wear rock climbing. Overbuilt to withstand the rigors of rugby, the shirt had a collar that would keep the hardware slings from cutting into his neck. It was blue, with two red and one yellow center stripe across the chest. Back in the States, Chouinard wore it around his climbing friends, who asked where they could get one.

Our company was growing, and we began to see clothing as a way to help support the marginally profitable hardware business. By 1972, we were selling rugby shirts from England, polyurethane rain cagoules and bivouac sacks from Scotland, boiled-wool gloves and mittens from Austria, and hand-knit reversible beanies from Boulder (no two were alike).

At a time when the entire mountaineering community relied on the traditional, moisture-absorbing layers of cotton, wool and down, we looked elsewhere for inspiration—and protection. We decided that a staple of North Atlantic fishermen, the synthetic pile sweater, would make an ideal mountain layer, because it would insulate well without absorbing moisture. But we needed some fabric to test out our idea, and it wasn’t easy to find.

Finally, Malinda Chouinard, acting on a hunch, drove to the Merchandise Mart in Los Angeles. She found what she was looking for at Malden Mills, freshly emerged from bankruptcy after the collapse of the fake fur-coat market. We sewed up some samples and field-tested them in alpine conditions. Synthetic pile had a couple of drawbacks, but it was astonishingly warm, particularly when used with a shell. It insulated when wet, but also dried in minutes, and it reduced the number of layers a climber had to wear.

It does no good to wear a quick-drying insulation layer over cotton underwear, which absorbs body moisture, then freezes. So in 1980 we came out with insulating long underwear made of polypropylene, a synthetic fiber that has a very low specific gravity and absorbs no water. It had been used in the manufacture of industrial commodities like marine ropes, which float. Its first adaptation to clothing was as a non-woven lining in disposable diapers.

Using the capabilities of this new underwear as the basis of a system, we became the first company to teach, through essays in our catalog, the concept of layering to the outdoor community: inner layer against the skin for moisture transport, middle layer of pile for insulation, outer shell layer for wind and moisture protection. It didn’t take many seasons before we saw much less cotton and wool in the mountains—and a lot of badly pilled powder blue and tan pile sweaters worn over striped polypropylene underwear.

Although both pile and polypropylene were immediately successful, we worked hard from the start to improve our quality and overcome the problems of both fabrics. We worked closely with Malden to develop first a softer bunting fabric, and eventually Synchilla®, an even softer, double-faced fabric that did not pill at all. While Malden’s access to capital made many of the innovations possible, Synchilla never would have been developed if we had not actively shaped the research and development process. From that point forward, we began to make significant investments in research and design.

Our replacement for polypropylene came in 1984. While walking around the Sporting Goods show in Chicago, Chouinard saw a demonstration of polyester football jerseys. Milliken, the company that made the jerseys, had developed a process that permanently etched the surface of the fiber as it was extruded, so that the surface became hydrophilic—it wicked moisture away from the body to the outside where it could evaporate. Chouinard saw the fabric as perfect for underwear, and Capilene® polyester was born.

In fall 1985, we shifted our entire line of polypropylene underwear to the new Capilene® fabric. It was a big risk, similar to our introduction of chocks in 1972. During the same season, we also introduced the new Synchilla fleece. The older products made of polypropylene and bunting had represented 70 percent of our sales. But our loyal core customers quickly realized the advantages of Capilene and Synchilla, and sales soared.

During the early 1980s, we made another important shift. At a time when all outdoor products were either tan, forest green or (at the most colorful) powder blue, we drenched the Patagonia line in vivid color. We introduced cobalt, teal, French red, aloe, seafoam and iced mocha. Patagonia clothing, still rugged, moved beyond bland looking to blasphemous.

Let My People Go Surfing

We began to grow at a rapid pace; at one point we made Inc. Magazine’s list of the fastest-growing privately held companies. That rapid growth came to a halt in 1991, when a recession crimped our sales and the bank called in our revolving loan. To pay off the debt, we had to lay off 20 percent of our work force—many of them friends and friends of friends. We had become dependent on growth we couldn’t sustain. Yvon took his top managers to Patagonia to reflect on the kind of business Patagonia should be.

We were able, in many ways, to keep alive our cultural values, even during the heavy-growth years, and after the shock of the 1991 layoffs. We were surrounded by friends at work who could dress however they wanted, even barefooted. People ran or surfed at lunch, or played volleyball in the sandpit at the back of the building.

The company sponsored ski and climbing trips for employees; many more trips were undertaken informally by groups of friends who would drive up to the Sierra on Friday night and arrive home, groggy but happy, in time for work on Monday morning.

Since 1984 we have had no private offices, an architectural arrangement that sometimes creates distractions but also helps keep communication open. That same year we opened a cafeteria that serves healthy, mostly organic food. The only thing that doesn’t change here is the beans and rice, served every Monday.

We also opened, at Malinda Chouinard’s insistence, an on-site childcare center—at the time one of only 150 in the country (today there are thousands, though still not enough). The presence of children playing in the yard or having lunch with their parents in the cafeteria helps keep the company atmosphere more familial than corporate. In 2015, we were recognized by President Obama for our commitment to working families.

Friends of the Ventura River

Patagonia was still a fairly small company when we started to devote time and money to the increasingly apparent environmental crisis. What we began to read—about global warming, the cutting and burning of tropical forests, the rapid loss of groundwater and topsoil, acid rain, the ruin of rivers and creeks from silting-over dams—reinforced what we saw with our eyes and smelled with our noses during our travels.

At the same time, we slowly became aware that uphill battles fought by small, dedicated groups of people to save patches of habitat could yield significant results. The first lesson came right here at home, in the early ’70s. A group of us went to a city council meeting to help protect a local surf break from a development plan. We knew vaguely that the Ventura River had once been a major steelhead habitat. Then, during the ’40s, two dams were built, and water diverted. Except for winter rains, the only water left at the river mouth flowed from the sewage plant.

At that city council meeting, several experts testified that the river was dead and that channeling the mouth would have no effect on remaining birds and wildlife, or on our surf break. Things looked grim until Mark Capelli, a 25-year-old biology student, showed photos he had taken along the river—of the birds that lived in the willows, of the muskrats and water snakes, of eels that spawned in the estuary. He even showed a slide of a steelhead smolt: yes, 50 or so steelhead still came to spawn in our “dead” river. The development plan was defeated.

We gave Mark office space and a mailbox, and small contributions to help him fight the river’s battle. As more development plans cropped up, the Friends of the Ventura River worked to defeat them, to clean up the water and to increase its flow. Wildlife multiplied and more steelhead began to spawn. Mark taught us two important lessons: that a grassroots effort could make a difference, and that degraded habitat could, with effort, be restored. His work inspired us.

We began to make regular donations to smaller groups working to save or restore habitat rather than give the money to NGOs with big staffs, overheads and corporate connections. In 1986, we committed to donating 10 percent of profits each year to these groups. We later upped the ante to one percent of sales, profit or not. We have kept that commitment every year since. The formation of 1% for the Planet in 2002 made it easy for other companies to do the same.

In 1988, we initiated our first national environmental campaign on behalf of an alternative master plan to deurbanize the Yosemite Valley. Each year since, we have undertaken a major education campaign on an environmental issue. We took an early position against globalization of trade where it means compromise of environmental and labor standards. We have argued for dam removal where silting, marginally useful dams compromise fish life. We have supported wildlands projects that seek to preserve ecosystems whole and create corridors for wildlife to roam.

Every two years, we hold a Tools for Grassroots Activists Conference to teach marketing, campaign and publicity skills to some of the groups we work with. The lessons shared by leaders and experts from the nonprofit and for-profit world were so well received that we published a book so more activists could benefit from them.

We also, early on, began initial steps to reduce our own role as a corporate polluter: we have been using recycled-content paper for our catalogs since the mid-’80s. We worked with Malden Mills to develop recycled polyester from soda bottles for use in our Synchilla® fleece. We assessed the dyes we used and eliminated colors from the line that required the use of toxic metals and sulfides. In 2007, we made our efforts public—the good and the bad—with the launch of the Footprint Chronicles.

Opened in 1996, our distribution center in Reno, Nevada, achieved a 60 percent reduction in energy use through solar-tracking skylights and radiant heating; we used recycled content for everything from rebar to carpet to the partitions between urinals. We retrofitted lighting systems in our existing retail stores and buildouts for new stores became more and more respectful of the environment.

When we commissioned an independent environmental impact assessment of four of our most-used fabrics, cotton was surprisingly the biggest villain—and it didn’t have to be. Farmers had grown cotton organically for thousands of years. Only after World War II did the chemicals originally developed as nerve gases become available for commercial use, to eliminate the need for weeding fields by hand. After several trips to the San Joaquin Valley, where we smelled the selenium ponds and saw the lunar landscape of cotton fields, we asked ourselves a critical question: How could we continue to make products that laid waste to the earth this way?

In the fall of 1994, we made the decision to take our cotton sportswear 100 percent organic by 1996. We had to go directly to the few farmers who had gone back to organic methods. And then we had to go to the ginners and spinners and persuade them to clean their equipment after running what would be for them very low quantities. We had to talk to the certifiers so that all the fiber could be traced back to the bale. We succeeded. Every Patagonia garment made of cotton in 1996 was organic and has been ever since—though we are beginning to experiment with recycled cotton.

Becoming Responsible

With the start of the new millennium and the 30-year anniversary of his company looming, Yvon Chouinard began writing a philosophical manual for employees to lean on as the company grew. That manual became the best-selling book Let My People Go Surfing: The Education of a Reluctant Businessman (2005, Penguin Random House). Motivated by the book’s success and our shared love of stories, Patagonia Books was formed, and its first title, Yosemite in the Sixties by Glen Denny, was published in 2007.

In January 2012, Patagonia became the first California company to become a benefit corporation—a legal framework that enables mission-driven companies like Patagonia to stay that way as they grow and change. We are also a Certified B Corporation. To qualify as a B Corp, a business must have an explicit social or environmental mission and a legally binding fiduciary responsibility to take into account the interests of workers, the community and the environment, as well as its shareholders. To maintain B Corp certification, we must update and verify our qualifications every three years.

Worn Wear—our used clothing and repair program—began as a blog started by Keith and Lauren Malloy in 2012. They envisioned a place for people to share stories about their favorite Patagonia products and the badges of honor—the rips, tears, patches and stains—that recall treasured outdoor memories. The stories were a tangible reminder of the value of durability over disposability. They inspired the company to expand its humble repair service into the largest garment repair facility in North America, construct a mobile repair truck out of reclaimed materials—so a small team could travel the country and repair people’s clothing for free—and start a full-scale used clothing business.

In 2013, Yvon Chouinard announced the formation of a venture capital fund to help start-up companies that place environmental and social returns on equal footing with financial returns. Dubbed Tin Shed Ventures®—after the original structure that housed Chouinard Equipment—this unique fund helps forward-looking entrepreneurs think and act long-term.

As we continued to get our own house in order, attention turned to our supply chain. We don’t own any of the factories that make our products, so we have limited control over how workers are treated and how much money they’re paid. The Fair Trade Certified™ Sewing symbol is an assurance that some of the money spent on a product goes directly to its producers and stays in their community. Patagonia, in partnership with Fair Trade USA, has been making clothes that provide this benefit since 2014. Fair Trade is a first step on the path toward paying living wages throughout our supply chain.

In February 2018, we launched Patagonia Action Works to connect our customers with the environmental action groups we support. People have volunteered their time, signed petitions and donated money to hundreds of non-profit groups around the world because of this dynamic online platform. Locally, our stores hold Action Works events to help build a deeper sense of community with the small, tireless and often underappreciated grassroots activists working in their neighborhoods.

Due to the urgency of climate change, we can no longer be satisfied with lessening our impact on the planet. We must begin healing it. Patagonia Provisions took the first step when it released Long Root Ale, a beer brewed with Kernza® grain for its carbon-sequestration potential. Adopting Regenerative Organic farming practices in our supply chain to grow fibers and food is the next big step. In late 2018, Yvon Chouinard and CEO Rose Marcario changed Patagonia’s purpose statement to reflect this shift: “We’re in business to save our home planet.”

September 2022: the Earth is now our only shareholder. Nearly 50 years after Yvon Chouinard began his experiment in responsible business, ownership of Patagonia is transferred to two new entities: Patagonia Purpose Trust and the nonprofit Holdfast Collective. Every dollar that is not reinvested into Patagonia will be distributed as dividends to protect the planet. “Instead of extracting value from nature and transforming it into wealth, we are using the wealth Patagonia creates to protect the source,” said Chouinard. “I am dead serious about saving this planet.”

This brief history is dedicated to all Patagonia and Chouinard Equipment employees, present and past. To learn more about what we do and how you can change your business for the better, check out these books:

Let My People Go Surfing by Yvon Chouinard

The Responsible Company by Yvon Chouinard and Vincent Stanley

Family Business by Malinda Chouinard and Jennifer Ridgeway

Tools for Grassroots Activists by Nora Gallagher and Lisa Myers

Some Stories by Yvon Chouinard